A rather irreverent look backward

All right, you got off at the wrong bus stop out of Baghdad, stepped into an Akkadian Mythos time portal, and landed in Sumer, approximately three thousand years before a guy named Yeshua entered the same way. You’re luckier—he popped out as an infant, whereas you are the same 21st Century misfit who started out from Millpot, Wisconsin. It took a while to get straight, but Portal Maintenance have made quite a few improvements. Not a miracle anymore, but working on it.

Oh, and sorry for the surprise, but you’re the intruder here. So if you’re unhappy with the service, a stay with the local al-Qaeda lodge fellows can be arranged for your return two months hence.

Get over the shock that harking back five millennia was not your idea of a holiday. There’s nothing you can do about it. Having benefitted from a generous orientation by your portal conductor (see left) who punched your ticket for a round trip, you and a handful of fellow portal-bashers were placed on a special barge and poled down the Euphrates River for your first taste of Sumerian city life. Awaiting your pleasure is the greatest collection of humanity known to exist (present time): the city of Uruk.

Get over the shock that harking back five millennia was not your idea of a holiday. There’s nothing you can do about it. Having benefitted from a generous orientation by your portal conductor (see left) who punched your ticket for a round trip, you and a handful of fellow portal-bashers were placed on a special barge and poled down the Euphrates River for your first taste of Sumerian city life. Awaiting your pleasure is the greatest collection of humanity known to exist (present time): the city of Uruk.

So, here you are among 40,000 round-headed, beak-nosed Sumerians barely a meter and a half tall, with no clue about your surroundings. We hope you dressed for the heat. Your hostesses have supplied you with an adequate supply of currency, with the admonition to use it wisely, for there will be no more until your departure. You can’t even bet on the horses (see explanation below). But rest easy, you’re in good hands. Industrious, competitive Sumerians, especially the Uruk kind, are a friendly and hospitable lot.

Enjoy your stay. At least, that’s what they told me the sign over the gate says.

Getting Around In Uruk

Uruk is accustomed to tourists from all over. Every day sees the arrival of one or more traders leading ox carts laden with trade goods. This sort of visitor will likely find shelter in the home of one of Uruk’s wealthy and hospitable traders or merchants. Inns and hotels have not yet been invented. The tourist must seek alternate means of shelter.

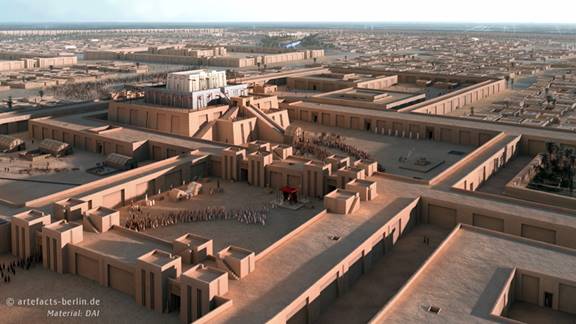

In doing so, most visitors get lost in the narrow winding streets of a city whose sprawl covers an incredible five-hundred acres (200 hectares).  A guide is advised. Any local willing to help for a shekel or two can be depended upon to lead you correctly to your destination.

A guide is advised. Any local willing to help for a shekel or two can be depended upon to lead you correctly to your destination.

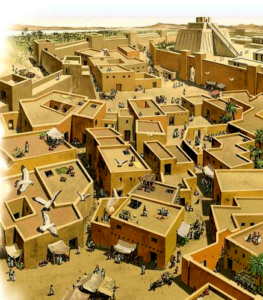

Uruk was not planned. It has grown haphazardly in all directions. Consequently, the traveler who wanders off the main avenues, of which there are but a few, finds himself in a maze of narrow, twisting, unpaved alleys, interrupted on occasion by a few wider paved streets, equally wandering. The vast majority of Uruk’s simple one or two-room whitewashed houses crowd these backstreets. Craftsmen such as carpenters, brick masons, laborers, and field workers occupy them.

The two-story houses of wealthy landowners and merchants claim the wider paved avenues. But wide or narrow, the streets of Uruk are typically strewn with trash and sometimes human waste, infrequently gathered by scavengers. Most of it is left to be trampled under foot. The sight and smell may repel travelers who have lived their lives in small villages or temporary campsites. Such is the price paid by city-dwellers for the privileges of job opportunity and security a city can provide.

Transportation

Horse-drawn carriage? Are you serious? This is 3,000 BC, and You Are There.

Sumerians haven’t invented the wheel just yet. They’re close with the potter’s wheel,  but axles and carts are a few generations off. Same for horses. All they’ve got are donkeys—you could straddle one of those little dog-sized guys while standing.

but axles and carts are a few generations off. Same for horses. All they’ve got are donkeys—you could straddle one of those little dog-sized guys while standing.

You will find your chief mode of transport at the ends of your own two legs. If you can afford a two-man litter and find one for hire, those fellows won’t get you anyplace much faster than you could walk yourself. Uruk’s throngs choke the narrow streets most hours of the day and make a litter more liability than asset.

You will find your chief mode of transport at the ends of your own two legs. If you can afford a two-man litter and find one for hire, those fellows won’t get you anyplace much faster than you could walk yourself. Uruk’s throngs choke the narrow streets most hours of the day and make a litter more liability than asset.

If you fancy floral delights, the abundant city gardens may be accessed by water taxi. Have no concern for the age of your “driver.” Many lads start as early as age six. There’s not much money in poling a skiff through Uruk’s network of canals, so most grown men prefer to work in field or shop.

You may find Uruk’s night life a lively venue. Taverns and cabarets are open every night and offer gaming, dancers, and singers. If companionship is your goal, you may find that too, at a price—one of the few things time never changes.

One of Uruk’s wonders is the temple bakery, and visitors are welcome—as long as you’re an early riser. The bakery pumps out 500 loaves daily to feed the needy and downtrodden. Besides bread, the bakery fashions barley cakes, sweet meats, and honeyed pastries. You may purchase directly from the temple store located on Way of No Locust, or at various shops throughout the city.

If you’re a religious person, you may welcome the dawn with Eanna’s high priestess at Morning Honors. Four other worship ceremonies take place throughout the day and evening. If you’re lucky you might catch the candlelight vigil following the supping hour—an ornate ritual full of song and homage to Goddess Inanna.

Accommodations

The level of comfort enjoyed by the upper classes may surprise the first-time visitor to Uruk. Houses of the merchant and trader class are large, at least two stories, occasionally three. As in most warm climates, they are built around a central courtyard where family life takes place. The ground floor rooms open onto the courtyard, while the upstairs rooms have a verandah overlooking the same domestic scenes. Door frames are painted red to ward off demons, an old superstition ingrained in Sumerians of all classes. Windows are barred with bronze.

Houses, temples, and public buildings are constructed of sun-dried mud bricks, wood being scarce (mostly imported from the Zagros Mountains). Stone is virtually non-existent in this alluvial world. Houses scarcely last one lifetime before needing repair or outright reconstruction. When the walls of a structure begin to appear unstable, workmen pull them down and trample the rubble flat to make a base for the new structure. As a consequence, Uruk has gradually risen over the centuries. The city now resides on a huge mound, the low hill travelers first see from a great distance.

Roofs require even more care. The only timber locally available is palm logs, used to form the roof support. Builders lay palm fronds over the logs as a base layer of packed and rolled dirt. After each rain, workmen climb on the roofs with stone rollers to repack the dirt surface.

Alternative Accommodation

The tourist who has not made prior business connections may encounter some difficulty finding a place to sleep in Uruk. The city can grow crowded at times, especially during the summer when the deserts and mountains seem to pour out a steady stream of immigrants seeking a better life in the city. At such times, travelers without a place to stay will be forced to camp outside the city alongside hundreds of hopeful (and out-of-work) immigrants.

Entertainment

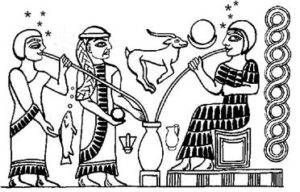

More experienced travelers make their way to the marketplace near the Temple Square, where a number of shops sell, among other tasty delights, a wonderful frothey drink called “beer.” Tables and chairs spill out onto the square, always crowded, every table usually taken up by men of all ages as well as a few women, drinking the deep amber liquid from large jars with five-foot drinking straws. Go in anyway, because someone will make room for you. Strangers are welcome.

Beer made from fermented barley and dates in a centuries-old tradition is, in many people’s half-joking opinion, the Sumerians’ greatest invention. Once you have imbibed a large jar of beer and enjoyed the camaraderie of the locals, you should have no trouble discovering a family with a free corner of their house where you can

Beer made from fermented barley and dates in a centuries-old tradition is, in many people’s half-joking opinion, the Sumerians’ greatest invention. Once you have imbibed a large jar of beer and enjoyed the camaraderie of the locals, you should have no trouble discovering a family with a free corner of their house where you can flop spend a few nights.

Crowds fill the square during all the daylight hours, sitting and talking quietly on benches, striving purposefully to meet someone, eating and drinking at food stalls, gambling over dice. Young people come to the square to meet their friends and make new ones. Visitors come to stare in wonder at the crowds. Diverse entertainment abounds–wrestling matches, story-tellers, magicians, acrobats, musicians, to name the more common.

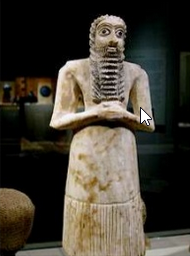

Sumerian men wear their beards long and part their hair in the middle, unless shaven. In warm weather, which is most of the time, they wear only a kilt-like wraparound garment below the waist, contented to go bare-chested. Sumerian women, who make themselves known in society and are self-assured in their role, generally wear their hair in braids coiled around the head like a hat, a very distinctive and attractive style. Their gowns are richly made, form-fitting, unabashedly catching the eye of every male who passes. They invariably leave their right arm and shoulder bare to allow freedom of movement.

Sumerian men wear their beards long and part their hair in the middle, unless shaven. In warm weather, which is most of the time, they wear only a kilt-like wraparound garment below the waist, contented to go bare-chested. Sumerian women, who make themselves known in society and are self-assured in their role, generally wear their hair in braids coiled around the head like a hat, a very distinctive and attractive style. Their gowns are richly made, form-fitting, unabashedly catching the eye of every male who passes. They invariably leave their right arm and shoulder bare to allow freedom of movement.

Food

The Time-Warped Tourist should have no problem finding food at reasonable prices. The land is highly productive and nearby marshes and the river itself provide a ready source of fish, fowl and small game. Uruk has no need to import food.

Most farm workers live in the city and venture out each day to tend their fields. Some of the wealthier landowners own villas outside the city, a place to get away from the crowds. The temples control much of the farmland surrounding Uruk, rented out for a share of the crops, part of which is used for trade and part stored in the temple granary to feed the impoverished.

Everything you could ever want can be found along the wider avenues and in the central marketplace. You can sample such delights as dates, beans, cucumbers, cheese, mutton, apples, melons, onions, garlic, turnips, flat bread, dried fish, pork, and duck. There are food stalls everywhere selling cooked food.

The Sumerians have conquered hunger, man’s age-old fear. It is the primary reason immigrants are attracted to the Land of the Two Rivers.

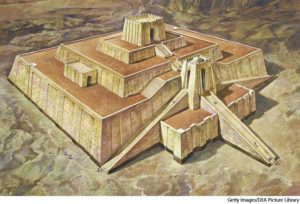

Religion: The Great Temple

The great temple Eanna is dedicated to Inanna, goddess of love, and later, war, and is quite easily the largest man-made structure in the known world. It is built on a raised platform from which you can see all over the city. You probably first noticed its peak protruding above the southern horizon from about ten miles upriver.

The platform is constructed from the remains of earlier temple buildings pulled down to make way for the new. With a powerful block-like appearance, Eanna commands an area large enough to support three dozen large houses.

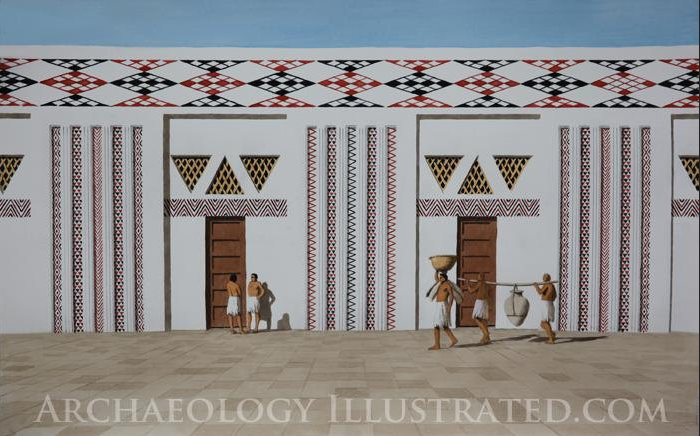

The interior has sixteen small private rooms situated around the perimeter of the building for the exclusive use of the Lukur priestesses. This leaves a large open cruciform shaped public ritual area. Huge cedar beams thirty-five feet long support the roof thirty feet above the paved floor. A rarity in Uruk, the cedar beams come from the vast forests of giant cedar trees that still grow in the coastal mountains of the eastern Mediterranean, a priceless resource of the land called Canaan.

White gypsum plaster covers the temple walls inside and out. Colorful geometric designs, reflecting the sun from what appears to be thousands of bright “eyes,” decorate the outside columns and walls. These are called “mosaics.” Artisans create them from thousands of small clay cones, dipping each one separately into red, white or black dye before shoving them into the still-wet plaster. It is a marvel to watch.

The artist must work fast, and there is no way to correct errors except to start again. Those who fail are force-fed brussels sprouts for thirty days. There is a Sumerian word for “yuch” but it will not appear here, as this is a family place.

Religious Practices

Your Sumerian hosts have hundreds of gods, not to mention local demons, spirits, and ghosts, far beyond the needs of a tourist on a short visit. However, visitors should make an effort to understand and respect the Sumerian worship of goddess Inanna. At almost any time of day you can expect to see worshippers bringing offerings to place before the life-size statue of Inanna in the sacred area at the far end of the great temple. A sensuous figure, naked, voluptuous, with arms slightly outstretched, she is the embodiment of life, the most precious and sacred commodity.

Your Sumerian hosts have hundreds of gods, not to mention local demons, spirits, and ghosts, far beyond the needs of a tourist on a short visit. However, visitors should make an effort to understand and respect the Sumerian worship of goddess Inanna. At almost any time of day you can expect to see worshippers bringing offerings to place before the life-size statue of Inanna in the sacred area at the far end of the great temple. A sensuous figure, naked, voluptuous, with arms slightly outstretched, she is the embodiment of life, the most precious and sacred commodity.

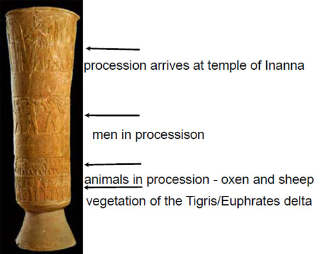

Tourists who remain in Uruk for more than a few weeks will likely see processions and rituals set to honor Inanna. Her priestesses appear as bare as their goddess, whose image they bring forth into the city on an ox-drawn sled. Try not to miss this spectacle, but if you’re short of time, at least examine the large vase at the head of the Eanna temple opposite the door. It is beautifully carved with scenes of offerings being presented to Inanna.

Though mortal, the Lukur priestesses are, like Inanna, consorts of Anu, god of heavens, father of all gods. Their daily human intercourse, which their vows demand, reflects their mystical marriage to Anu and sisterhood with Inanna. The high priestess, or Entu, the first wife of Anu, oversees their devotions. Theirs is an honorable religious profession, for which any Sumerian father and mother would be proud.

Though mortal, the Lukur priestesses are, like Inanna, consorts of Anu, god of heavens, father of all gods. Their daily human intercourse, which their vows demand, reflects their mystical marriage to Anu and sisterhood with Inanna. The high priestess, or Entu, the first wife of Anu, oversees their devotions. Theirs is an honorable religious profession, for which any Sumerian father and mother would be proud.

Fortunately, no souvenir pictures are allowed. Selfies are right out.

Your Farewell to Uruk

As you embark on your river barge for the long return to the time portal, you are given the V.I.P. treatment. A Sumerian lovely drapes garlands of flowers about your neck as the civic leaders gather about your small entourage. The high priestess of Eanna, who is also the temple queen, or Entu, favors each in your party with a small gift box, to be opened only upon your arrival home.

Today, authorities consider this ancient tradition to be the precursor to today’s hated “Do Not Open Until Xmas.”

Thing is, by the time you get yours home to good old Millpot, it’ll be 5,000 years old. You’ll be in possession of either a priceless relic that will finance your kids through Harvard, or a pile of smelly dust. But hey, you’ll always have the memory of your Time-Warped Tour of ancient Uruk.

In the immortal words of King Ur-Nammu, shebun gulla abzu Narnia.

Don’t ask me what it means. Some Twentieth Century Irish author plagarized it.